workshop

Description of key Kubernetes objects

| toc | prev | next |

Here we describe some of the key OpenShift objects and explain what happened in the last exercise.

In the last exercise we just told OpenShift the name of a container image to use and then a lot of magic happened.

We’ll now explain some of this magic.

Pods

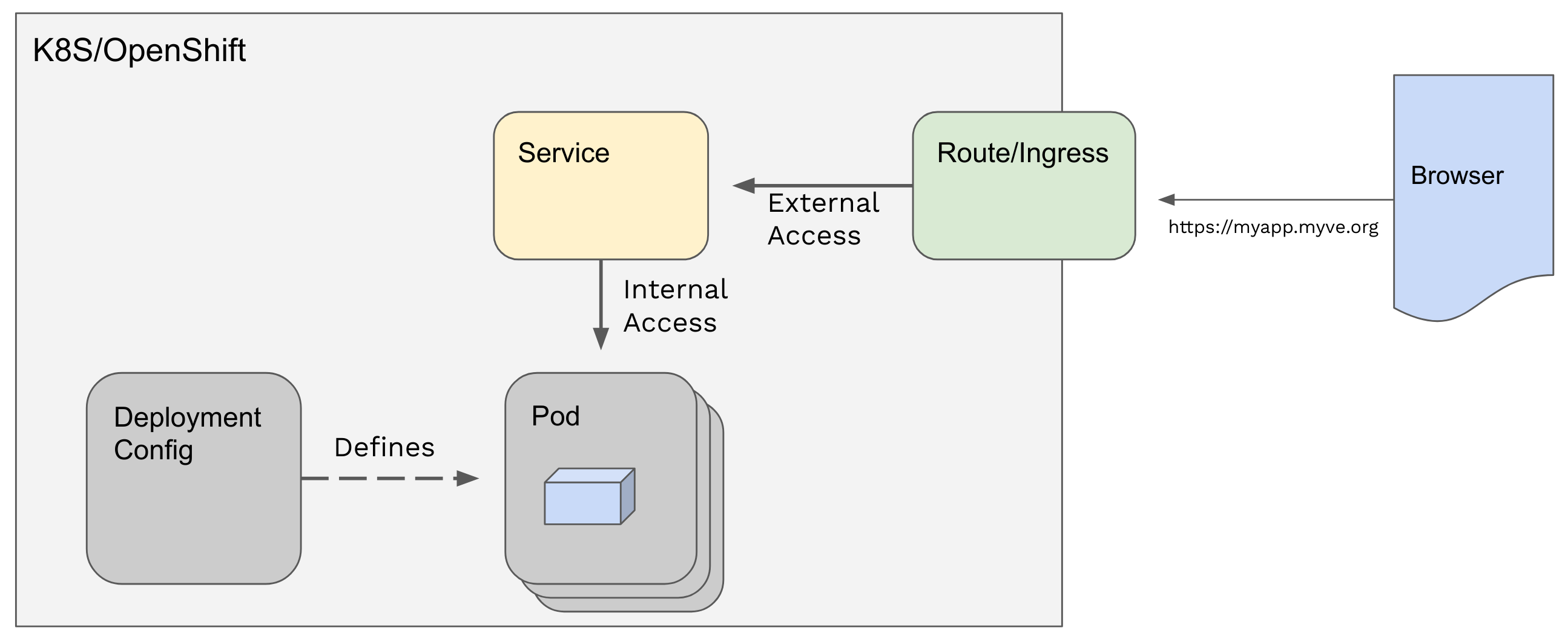

In Kubernetes containers run as Pods. A Pod is a wrapper for one or more containers. The Kubernetes controllers interact with Pods, which themselves control the containers running in them. In many cases a Pod runs a single container and that Pod can be thought of as the running container.

Deployments

We can start and stop pods using the API, but we don’t usually do that. Instead we create a DeploymentConfig (or a Deployment) that describes the deployment of a pod. The DeploymentConfig acts as a specification for what is expected for the pod ensuring it is behaving as required.

For instance, if the pod crashes Kubernetes will restart it. If you tell the DeploymentConfig that you want 3 replicas of your pod then OpenShift will try to ensure that there are 3 running. If you had created a ‘bare’ pod then none of this would happen - if the pod crashed it stay crashed until you noticed and manually re-created it.

Note that in vanilla Kubernetes (as opposed to OpenShift) you will likely use Deployments as DeploymentConfigs are an OpenShift specific extension, but there is very little difference.

Services

We just introduced the concept of scaling an app through having multiple replicas. Maybe your pod is providing an API that other pods want to use, and usage meant that one pod could not handle all of your requests. Or maybe you wanted some resilience so that if a pod crashed there was another identical one running that could still handle the requests whilst the crashed pod was being replaced.

But how would that another application know where the pods were?

This changes over time as your pod was scaled up or down or as OpenShift relocated to the pod to a different server. To address this you don’t access pods directly, you do this through a Service which acts as a load-balancer for the pods, and keeps track of where the pods are. That way you just access the Service which has a location that doesn’t change. The Service redirects your request to one of the pods it is serving.

Routes

A Route directs traffic from outside the OpenShift cluster to the service. The service allows traffic from within the cluster to arrive at the pod, but for traffic from outside the cluster you need a Route that acts as a proxy for the service.

When we created the PySimple app through the web console in Exercise A what happened is that OpenShift created a DeploymentConfig for the PySimple pod, set the number of replicas to 1 (as well as a number of other default parameters) and created a Service for that pod.

You’ll recall that in Exercise A we also manually created a Route for the Service.

When you created the PySimple app OpenShift doesn’t know whether you want to route traffic from outside, and assumes you don’t. Hence why you need to manually add the route yourself.

Note that in vanilla Kubernetes (as opposed to OpenShift) you will likely use Ingress as Routes are an OpenShift specific extension, but there is very little difference.

Summary

The diagram above shows the relationship of the Pod, the DeploymentConfig, the Service and the Route.

Creating object instances - Templates, Parameters and Objects

The most common way to create OpenShift objects like DeploymentConfigs and Services is by providing a definition in JSON or YAML format (YAML is much more friendly so we use this throughout the workshop). For instance you can define a DeploymentConfig for our PySimple application like this:

apiVersion: apps.openshift.io/v1

kind: DeploymentConfig

metadata:

name: pysimple

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

name: pysimple

template:

metadata:

labels:

name: pysimple

spec:

containers:

- image: alanbchristie/pysimple:2019.4

name: pysimple

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

protocol: TCP

You can then use that YAML definition to create the DeploymentConfig. This could either be done using the web console or the CLI. We’ll do this in a later exercise.

You will notice that in that DeploymentConfig definition all the values are hard-coded into the definition. This is not very flexible as you sometimes need to parameterise the deployment. To handle this you can instead use Templates that allow to define parameters that can be set at deployment time. A template for the DeploymentConfig we just looked at could look like this:

kind: Template

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: pysimple

labels:

template: pysimple

parameters:

- name: NAME

value: pysimple

- name: IMAGE

value: alanbchristie/pysimple:2019.4

objects:

- kind: DeploymentConfig

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: ${NAME}

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

name: ${NAME}

template:

metadata:

labels:

name: ${NAME}

spec:

containers:

- image: ${IMAGE}

name: ${NAME}

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

protocol: TCP

We won’t go into details of the syntax at this stage, but just point out some basics. There are 2 key sections here.

The first is the parameters which define the parameters that can be set. These can have

values in the template which act as defaults, but these can be overridden when you deploy allowing you to specify

different values. For instance the IMAGE parameter is defined and set to a default value of

alanbchristie/pysimple:2019.4.

The second section to consider is the DeploymentConfig object that describes the DeploymentConfig.

You will notice that it is quite similar to our original definition, but that the values of many of the properties

come from the parameter values. For instance the container image property is set to the value of the IMAGE

parameter that will have the value of alanbchristie/pysimple:2019.4 unless we provide a different value when we deploy.

Next we will look at how to deploy PySimple using templates and the CLI.

| toc | prev | next |